On Not Being Transparently “Oveir Bottle” in South-Central New Jersey at Rosh Hashanah Time

Rabbi Hillel L.Yarmove

My many years of writing and traveling have convinced me that undoubtedly there’s plenty to learn wherever you find yourself, if only you’ll allow your imagination to unwind. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to do some research beforehand so that you choose interesting places and scintillating experiences.

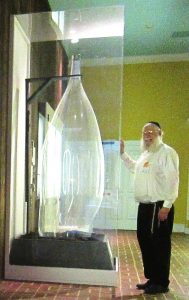

Take the town of Millville, New Jersey, for example, located at the head of the Maurice River in the south-central portion of the Garden State, about an hour-and-a-half drive from Lakewood. Historically, a major glassmaking center (allegedly, only Pittsburgh, PA, was more productive by the end of the nineteenth century), Millville is home to the Wheaton Arts and Cultural Center. Established in the early 1970s, this intriguing “arts community” hosts (among other things) a glass-making unit, as well as a ceramics and flame-working studio. Its Museum of American Glass is the biggest of its kind in the entire United States. And within the confines of the Museum is the world’s largest bottle.

Now, I originally chose Millville as an exploration site because of that colossal bottle (see picture)—or so I had thought. But I soon came to realize that there was something about bottles in particular and glass in general that was energizing me to travel all the way to Millville to visit this artistic gem of an educational complex at this spiritually crucial time of year.

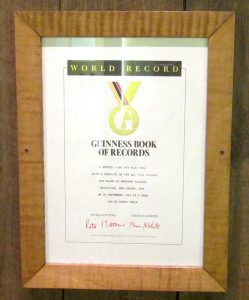

Standing next to that world-class glass container, I was startled to realize that in many ways we are very much like that colossus. Rearing our heads skyward, we imagine ourselves to be self-important to an extreme, forgetting for the moment that attribute of humility that we are “no more than utensils filled with bushah uchelimah.” And, in the final analysis, how fragile we all are! Indeed, the Guinness-World-Record bottle itself had to be protected by a massive, extremely secure case—lest some overenthusiastic glass-lover might decide to give it one clap too many, thus shattering the dreams and Herculean efforts of the glaziers who had crafted it.

Prior to visiting the Museum of American Glass, I had gazed raptly at the glass-forming process in action at Wheaton’s glass studio. Watching the glass being formed and heated up in “garages” (kilns) at over 2000 degrees Fahrenheit, how could I not allow the words of the selichah from Yom Kippur night to waft through my mind: : “Ki hinei kazechuchis b’yad hamezageig: birtzoso chogeig uvirtzoso mimogeig; kein anachnu b’Yadcha, Ma’avir zadon v’shogeig. . . .: “For behold like glass in the hand of the glazier, [who] at will forms the glass or melts it down; so too are we in Your hand, O One Who forgives intentional and unintentional sins . . . .”*

Pelledig!

Leaving the Wheaton Center with a newly enhanced appreciation of the brittleness and transparent quality of human life, I could now more sincerely pray that all Klal Yisrael be granted total mechilah and kapporas avonos for the coming year, one in which no one will be “oveir bottle” either in ruchniyos or in gashmiyus.

Kesivah vachasimah tovah, dear readers!

Questions or comments? I may be reached at hillyarm@yeshivanet.com.

You must be logged in to post a comment.